Learning a machine to feel emotions

Published:

The human singularity lies in his ability to experience emotions

In the 1980s, when the unique nature of humanity was debated, the game of chess was usually cited as the ultimate proof of human superiority. On February 10, 1996, IBM’s Deep Blue defeated world chess champion Garry Kasparov. 20 years later, AlphaGo defeated Lee Sedol in the game of Go, considered far more complex than chess. Today, we no longer talk about human superiority but about our uniqueness. It would reside in the subtle mix of our emotions. The machine is not capable of feeling, of experiencing. Watching a movie, the machine can see, can count the characters, predict their trajectory, … but does not “feel” the beauty of it. Hold on. Are we sure about this?

How to qualify an emotion?

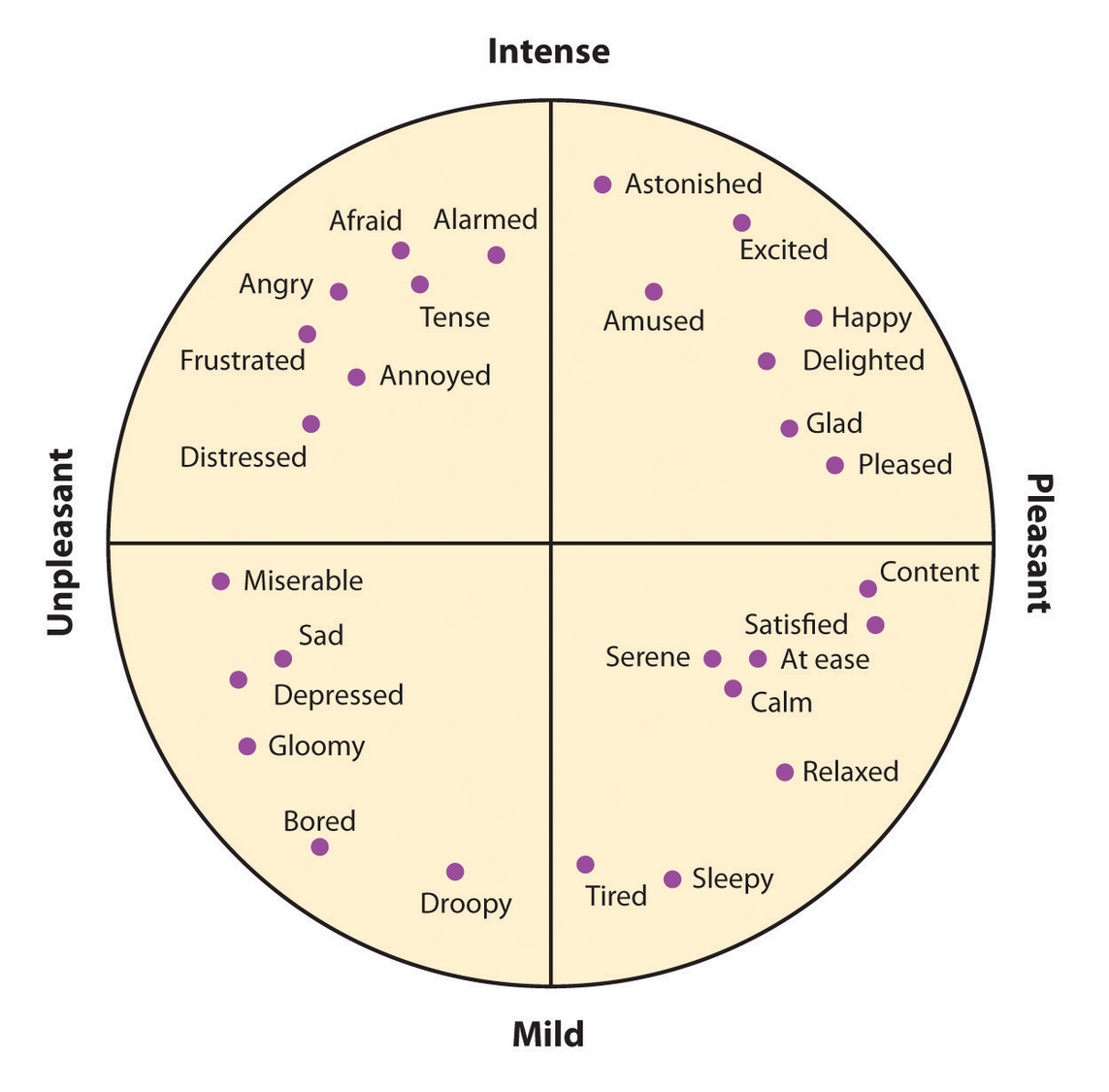

A simple but satisfying model consists in describing emotions in the circumplex model. The circomplex model defines all emotions with two values: valence and arousal. Here are a few examples:

Angry is unpleasant and intense, let’s describe angry with (valence = 0.9, arousal = -0.8).

Can we imagine a machine that predicts the emotion the average viewer feels when watching a movie? It’s starting to look like a prediction problem. Deep learning enthusiasts are beginning to imagine a dataset of films annotated with the emotion felt by the viewer over time. That’s exactly what it’s all about.

The 2018 version of the MediaEval dataset consists of raw video data from film footage under Creative Commons license, and features extracted from the images and soundtrack. The data are obviously labeled every second in the valence-arousal plane. In total, there are 31 hours of film. The challenge for us is therefore to learn a model that predict the emotions induced in a viewer by the image-audio combination of the data.

You will tell me that emotion is subjective. Yes, it is. But it is reasonable to think that the same scene will produce similar emotions in most of us. Did you feel joy when you looked at Mufassa’s gif? So we’ll take the average of 10 annotators, and we try to predict the average emotion felt.

Model and results

To capture the temoral and special dimensions, we chose a rather classical architecture composed of CNN and LSTM layers. As input we do not use raw data (pixels) but descriptors. For some, there is a spatial meaning. It is in these cases that we will assign a CNN layer.

I have presented you with one of the three approaches that have been explored. None of these three approaches has yielded good results. To put it simply, the three models are roughly equivalent to a model that systematically output the average emotion out of the dataset. How to interpret this difficulty in making the model converge? Are we bad? It is unlikely, since our score is close to the scores obtained by the other participants in the MediaEval contest.

First hypothesis: the emotion signal is absent from the descriptors. The emotion signal cannot be absent from films (since they produce emotions in us). But, at the input of our models, we have audio and video descriptors. It is likely that this descriptor exaction stage destroys the emotion signal. To solve this problem, the models would have to take the raw images as input. The computational costs would be much higher, but this could yield results.

Second hypothesis: the annotation is too noisy to obtain a usable dataset. In practice, it is quite complex to correctly annotate the emotion felt. You have to look critically at what you feel. The annotator has to stop watching every 5 seconds to say what he feels. This interrupts the continuity of the action. Moreover, it’s complicated to distinguish between what we feel and what we think the filmmaker wanted us to feel.

What do you think?